Reps

I got into poker in 2003, the same time everyone else did.

That was the year an accountant from Tennessee named Chris Moneymaker won the $2.5M main event at the World Series of Poker, beating out 3,000 other players, many of them professionals. A buy-in to the WSOP Main Event costs $10,000, but Moneymaker (yes, his real name) earned his seat by winning a $40 online tournament on PokerStars.

An amateur named Moneymaker turned $40 into $2,500,000 on ESPN... and online poker boomed.

At the time, Doyle Brunson was one of the best poker players in the world. From his Wikipedia page:

Brunson was the first player to win $1 million in poker tournaments. He has won ten WSOP bracelets throughout his career, tied [for second all-time]... He is also one of only four players to have won the Main Event at the World Series of Poker multiple times, which he did in 1976 and 1977. He is also one of only three players... to have won WSOP tournaments in four consecutive years....

Doyle was born in 1933. He started playing professionally in the 1950s, after a knee injury derailed his basketball career, and after he made more in a single night playing cards than he was going to make all month at his office gig. In the 1950s and 60s, he drove across Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana to play in the big money games, often run by organized crime. He moved to Vegas in 1970s. By the time poker got big in 2003, Doyle Brunson had been playing for nearly 50 years.

In live poker – poker played IRL with a real cards and chips – you'll average around 30 hands per hour with a competent dealer. Let's say that by 2003, Doyle had been playing for 50 years, 50 weeks a year, 5 days a week, 10 hours a day, 30 hands per hour. That adds up to 3.75 million hands in his lifetime. When the poker boom hit, Doyle was among the best, in part, because he'd played more hands than anyone else.

Then the internet happened.

The pace of live poker is constrained by the time it takes to shuffle, deal, and count chips. In an online poker room, where the mechanics happen automagically, you see at least double the number of hands per hour.

In online poker, there's a game going 24 hours a day, seven days a week. You don't have to drive across the state, and you don't have to wait until evening for the action to start. On the internet, there's always a game and never a commute.

In live poker, you can only play one table at a time because, you know, it's physically impossible to sit at two tables at once, laws of physics being what they are and all. In online poker, it's common for professionals to play four or more (!) tables simultaneously.

Let's say that you're a 16 year old kid in 2003. You watch Chris Moneymaker win the World Series of Poker, you borrow your parent's credit card and put $50 into PokerStars. You get addicted, you're talented enough to not go broke, you have no real responsibilities, and basically spend all your free time playing online. Let's say you average 50 weeks a year, 7 days a week, 12 hours a day, and are quad-tabling at 60 hands per table per hour.

That's one million hands per year.

By the time you reach the ripe age of 21 and sit down to your first WSOP, you've played more hands than Doyle Brunson.

In 2008, Peter Eastgate won the main event, beating out 6,843 opponents for a prize of over $9,000,000. He was 22 years old, making him the youngest player ever to win the tournament. He held that record for... one year.... until Joseph Cada won at the age of 21 in 2009.

Digital practice lets people get better faster. A lot faster.

Photography is the area in my life where I've been thinking about this most recently. Three years ago, my friend Doug McKenzie gave me a Canon 5D Mk II DSLR that had been collecting dust on his shelf. Though the model has changed, I've carried a camera with me every day since.

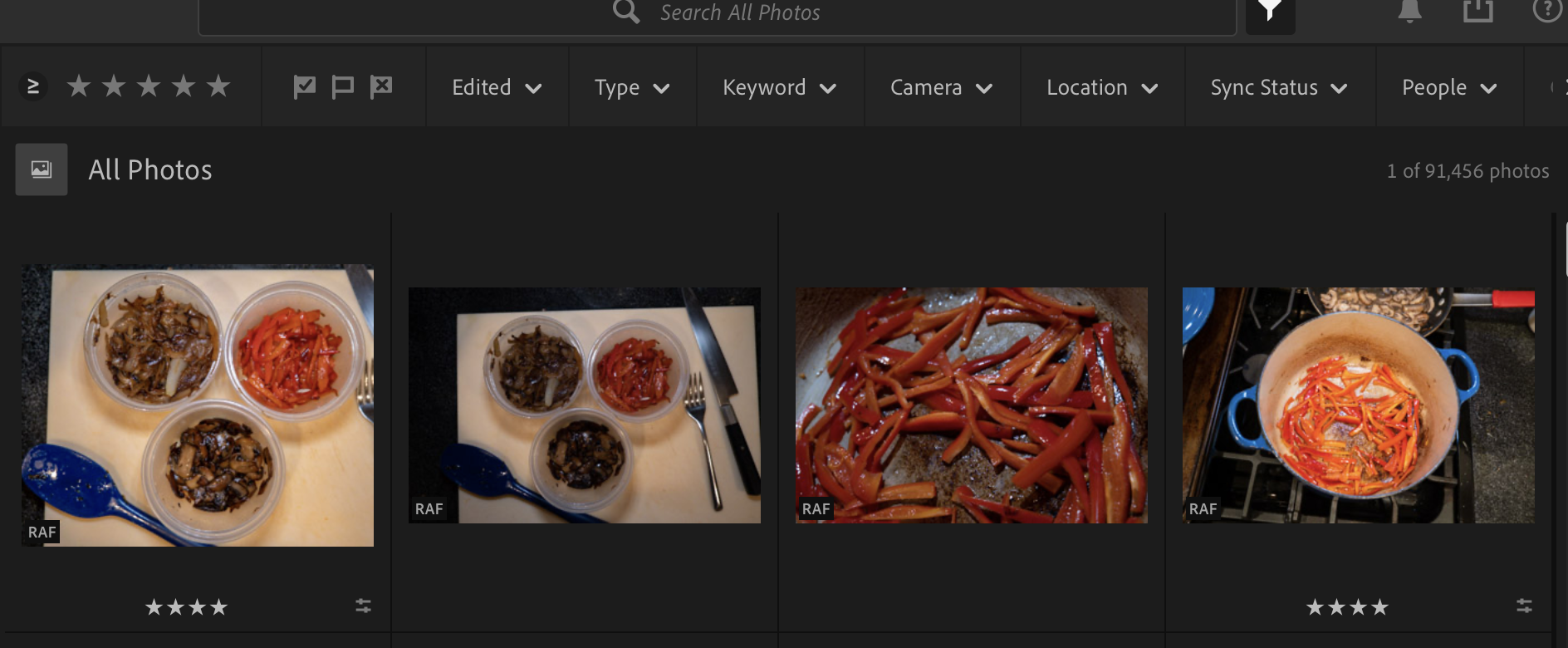

Every few nights, I use an app called Photo Mechanic to quickly cull the images from my SD cards. I keep the pictures that are "in frame and in focus" – about 1 in 3 – and import them to Lightroom for editing. The rest I delete, as to not clog up my cloud storage. As of tonight, Lightroom tells me that it's holding 91,000 photos, which means I've shot and processed ~270,000 frames over the last three years.

Back when I was a kid, I had a point-and-shoot 35mm camera. Let's say it costs $5 to develop a roll of film, and a roll of film has 24 frames. To process an equivalent number of photographs on an analog camera would cost ~$50,000. It's safe to assume that number would be prohibitively expensive.

That's to say nothing of the feedback loop. When I shoot digital, I set my settings, take a photo, and see right then and there if the photo was any good. I adjust the settings, and try again. As opposed to pressing the shutter and getting images back a few days later and hoping that I wrote down the settings each frame was shot with.

Then there's the knowledge sharing. I post my photos on Instagram, and Doug leaves comments like, "great leading lines," and I go google to see what "leading lines" means. On IG, I see the work of New York photographers who are far more talented than I am, then ride my bike to the same location to replicate the shot.

Digital photography has allowed me to reach a level of proficiency in three years that would have been impossible as a hobbyist photographer twenty years ago.

Where else is this phenomena playing out? Chess? Video production? Crafting influential ideas via Twitter? There's a bunch of areas right now where 20 year olds have gotten more reps and gained more proficiency than the most respected professionals of the generation before them, because their practice started online.

Where are you seeing this play out?

Photo is of my great friend Aram Reed, a personal chef in Chicago, who I met at a home game in 2005. Aram deals more than 30 hands per hour.